Ford’s Chicago Assembly Plant Turns 100

June 3, 2024

Ford’s Chicago Assembly Plant Turns 100

June 3, 2024During the post-war boom years, the plant assembled Ford Crestline sedans and F-100 pickup trucks.

Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

Chicago has been the home of ASSEMBLY since the first issue of the magazine rolled off the printing press in 1958. Back then, the area’s numerous factories were humming with activity. Plants such as International Harvester, Pullman and Western Electric were world-class operations that mass-produced tractors, railroad cars and telecommunication products.

Sadly, those large facilities closed their doors decades ago. But, one factory that was thriving in the late 1950s is still going strong today: Ford Motor Co.’s Chicago Assembly Plant on the city’s Southeast Side.

The facility is celebrating its centennial this year. Aside from being the largest manufacturer in Chicago today, it holds the distinction of being Ford’s oldest continuously operating production facility.

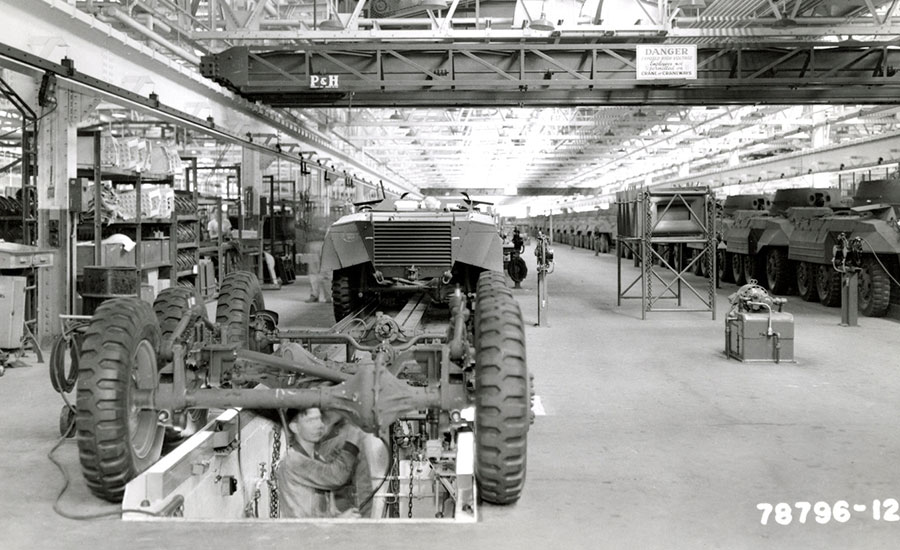

The Chicago Assembly Plant has withstood the Great Depression, World War II and the Covid pandemic, plus changing consumer tastes, labor strikes and supplier shortages. Along the way, the factory has produced a wide variety of vehicles, including Model A sedans, M8 armored military vehicles, F-100 pickup trucks, Country Squire station wagons, Galaxie 500 convertibles, Mercury Marquis sedans, Thunderbird coupes and Taurus sedans.

The 100-year-old plant located along the Calumet River has been retooled multiple times over the years to keep up with the latest car styles and the newest production equipment. The first cars that rolled off the assembly line in 1924 were Model T’s. Today, the historic facility assembles sport utility vehicles (SUVs) such as the Ford Explorer, Lincoln Aviator and Police Interceptor.

Pioneer Plant

Ford has a long history in Chicago that predates the current plant (see How the Model T Was Assembled in Chicago). Back in 1905, the company built a two-story dealership at 1444 S. Michigan Ave.

An article in a 1908 issue of the Ford Times, an employee newspaper, claimed that the showroom was among the company’s most important locations, stating: “Chicago is one of our largest branches and this year will dispose of more than a million dollar’s worth of Model T’s.”

Because of growing demand for the Model T, the automaker established a network of small auto plants located beyond its main operation in Detroit. The satellite factories were an early attempt to decentralize production and reduce transportation costs.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

Due to unprecedented popularity, year-over-year production of the Model T increased by approximately 80 percent during the first few years after the “people’s car” was launched in 1908. It then jumped to 125 percent in 1912 and 140 percent in 1913.

The original power house is visible on the left side of this recent view of the Chicago Assembly Plant taken from a boat in the Calumet River. However, dock cranes are long gone. Photo by Austin Weber

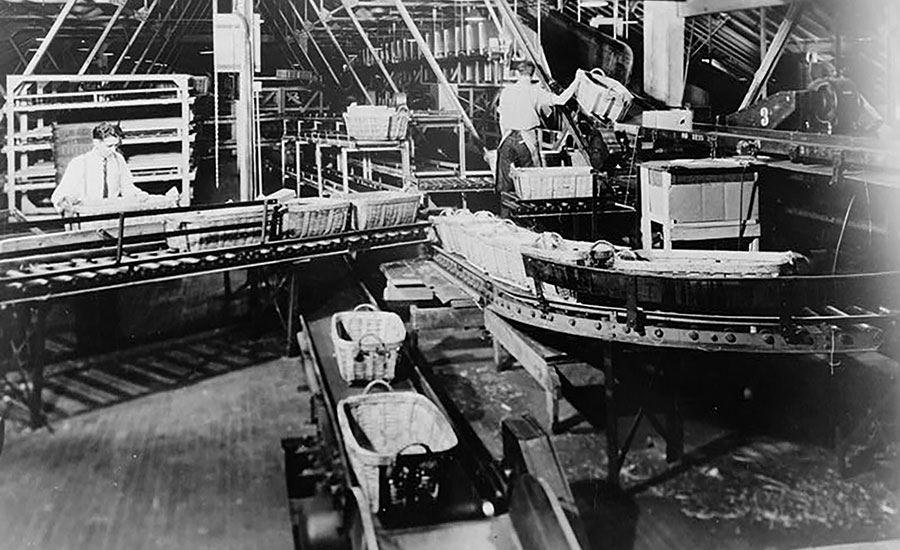

One of Ford’s first branch factories opened on the South Side of Chicago in 1914. The six-story brick building was located at 3915 S. Wabash Ave. Inside, a team of 500 workers assembled an average of 175 cars a day.

Parts shipped by rail from Ford’s Highland Park factory in Detroit were delivered to the upper floors of the building, where vehicles were put together using a top-down assembly process. Tin Lizzies rolled out a door on the ground floor, either for sale in the branch plant’s showroom or for distribution to regional dealerships in northern Illinois and Indiana.

That production method eventually proved to be inefficient to meet growing demand, so Ford purchased a large tract of land on the Southeast Side of Chicago in 1920 and began constructing a state-of-the-art factory the following year.

The 66-acre site was chosen for its strategic location along the main line of the Nickel Plate Railroad, which ran between Chicago and Buffalo, NY, via Cleveland. The triangular plot was located on the east bank of the Calumet River, a major industrial waterway flowing into the south end of Lake Michigan.

The riverside location enabled Ford to optimize production and distribution processes. It provided an easy way to bring in raw materials, such as lumber from the company’s saw mills in Northern Michigan. At the time, many parts of the Model T were made from various types of hardwoods, including its frame, floor boards and wheels.

Several steel mills were also located along the Calumet River just north of the Ford plant, such as large complexes operated by Republic Steel Corp., U.S. Steel Corp. and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co.

In addition, during the car manufacturing boom of the 1920s, many automakers shipped vehicles by ship through the Great Lakes. That’s because autorack rail cars commonly used today had not been invented yet. Automobiles were often shipped in box cars, but loading and unloading them was a time-consuming process.

The $6 million Chicago factory was designed by legendary architect Albert Kahn, who was the mastermind behind other Ford facilities, such as the Highland Park and Rouge plants in Detroit. Because the old multistory branch factory on Wabash Ave. was inefficient for moving material, Kahn designed a one-story building that could accommodate a moving assembly line and other state-of-the-art production equipment.

The Chicago plant shared several characteristics with other large Ford facilities. For instance, its riverside footprint closely resembles factories in Dagenham, England (located on the River Thames) and Cologne, Germany (located on the Rhine River). Docks and cranes could accommodate either cargo ships or barges.

Another trait similar to some of the automaker’s other factories was an on-site powerhouse where steam generators produced electricity to drive conveyors and machinery.

Modern Marvel

According to an article that appeared in the Nov. 15, 1923, issue of Ford News, “the new structure represents the culmination of years of specialized effort on the part of the Ford Motor Co. to evolve factories in which the most efficient methods of handling materials and assembling automobiles would be possible….

“One of the most elaborate conveyor systems of any Ford plant is being installed. This will carry parts from freight cars to storage rooms and thence to the main assembly lines where they are used….

“In addition to the regular branch assembly work, the Chicago plant is being equipped to build 250 closed car bodies in 16 hours. This will include the making of upholstery and enameling. Latest type body ovens, heated by oil burners, are being installed….

“It is of one story construction because it is the belief of Ford engineers that more economical handling of stock is possible on one floor than in the building of more than one floor level.

“The interior has been laid out not only from the standpoint of the most efficient arrangement, but also to present as attractive an appearance as possible. No unsightly wiring or shafting will obstruct the working spaces. Electric motors directly applied to the machinery and supplied current by conduits concealed in the floor will make belts unnecessary….

“In lighting arrangements, this plant probably excels any other in the country. Daylight reaches every part of the great floor space….

“The main assembly line runs down the center of the building with ‘feeder’ conveyors approaching it at right angles. These are for the movement of stock from storage bins….”

When it began production on March 3, 1924, the 640,000-square-foot Chicago Assembly Plant was Ford’s second largest factory and its biggest facility outside Detroit. The state-of-the-art building located at 12600 S. Torrence Ave. covered 11 acres.

An article in the Dec. 1, 1924, issue of Ford News proclaimed that the Chicago plant “is now employing 2,241 men and has a 345-car production a day.”

The new factory helped Ford boost production capacity, squeeze costs and achieve unprecedented economies of scale. For instance, by 1925, the price tag of a Model T Runabout was $260 vs. $900 in 1910.

After the last Model T rolled off the Chicago assembly line in June 1927, the factory was retooled to produce a highly anticipated replacement dubbed the Model A. However, it was replaced by the Model B when production of the popular V8-engined car ended in 1931.

During World War II, the Chicago Assembly Plant built armored vehicles for the U.S. Army. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

Somber Years

During the Great Depression, Ford was forced to shutter most of its factories. The Chicago operation was one of 11 facilities that remained open, but production was interrupted amidst periods of economic turmoil and labor unrest.

One bright spot during the dark decade occurred in the summer of 1933, when the Century of Progress Exposition brought millions of visitors to Chicago’s lakefront. During the world’s fair, the Ford factory opened its doors and allowed people to get an up-close look at the automobile assembly process. The company operated a fleet of 20 white courtesy sedans that transported people back and forth between the Congress Hotel and the plant.

The Ford tour was in response to a popular exhibit at the world’s fair sponsored by General Motors. The automaker’s pavilion featured a working assembly line that produced Chevrolet sedans using workers who were idled by the temporary shutdown of its factory in Janesville, WI. Due to popular demand, the fair was extended into 1934 and Ford sponsored a pavilion of its own.

An article that appeared in the December 1937 issue of Ford News, provided a glimpse of what life inside the plant was like in that era: “Built 13 years ago, the present Chicago assembly plant looks more like a modern high school than an industrial establishment….

“So far-sighted were the designers of the building that even today it has features which are distinctly modern. Consider such a factor as daylight inside every corner of the vast floor. Eight acres of glass, principally in the roof, make this possible.

“Long and low; built of red brick, with a mosaic effect of white face brick interposed with red near the top; the many windows, always clean; the traditional Ford water tower; a power plant with large, tall smokestack; the well-kept green lawn surrounding the building, the plant presents a panorama of beauty in modern industry.

“The building is 1,363 feet long and 500 feet wide. Two loading docks for freight cars run the entire length on each side. In the northwest corner, a large display room faces Torrence Avenue, Route 330, one of the main highways into Chicago from the south and east….

“Body construction occupies a large section, centrally located on the western side of the building. In the extreme southwestern corner, rear axles and drive shafts are assembled—the start of production. Frames join the line about 100 feet from the corner; shortly after, the front axles are added.

“Moving north, through the center of the building runs the main chassis line. The frames, being turned right side up, are dropped on the conveyor which moves at the rate of 24-and-a-half-feet a minute. The motor, radiator, front fenders and grille are added to the frame as the car begins to take shape.

“The bodies, completely finished, move from the north to a point about two-thirds distance from the north wall. Here, they are hoisted and dropped onto the chassis line where they are bolted to the frame, wheels put on, lights hooked up and brakes adjusted as the finished car reaches the end of the line. Peak production of the plant is 600 cars a day.”

The 1940s was a decade of change, dominated by World War II production mandates and historic labor union agreements. To secure an adequate supply of raw materials vital to the war effort, the last civilian vehicle was assembled at the Chicago plant in March 1942.

By that time, Ford had received a request from the U.S. Army “to design a vehicle with all the speed assets of an automobile, fire power of a light tank, armor, and enough equipment and crew accommodations for a scouting trip of several days.” The light-armored vehicles were assembled at the Chicago Assembly Plant and the Twin Cities Assembly Plant.

After retooling, both Ford facilities began producing M8 Greyhound scout cars and M20 utility vehicles. Each vehicle contained armor plating and six wheels for traveling over all types of terrain.

A special test track was built beside the plants to run the reconnaissance vehicles through a series of rigorous high-speed maneuvers before being shipped to battlefields in Europe and the Pacific theatre, where they served at the Battle of the Bulge, the Battle of Okinawa, the Normandy invasion and other epic sites.

To expedite production, the M8 used as much existing components and equipment as possible. For instance, the axle and driveshaft assemblies were essentially the same as those found in Ford trucks. However, machine gun turrets and 37-millimeter cannons were attached to the top of the 8-ton vehicles, which had a top speed of 56 mph and housed a crew of four soldiers.

Booming Business

By the end of 1945, peacetime activity resumed at the Chicago Assembly Plant. The first pickup trucks rolled off the line in September, marking the facility’s return to civilian production. Then, on Dec. 6, the first passenger car, a two-door Mercury Sedan, was made in the factory.

In 1946, operators celebrated after signing a landmark agreement with the United Auto Workers (UAW) union that made Ford employees that highest paid in the auto industry.

Due to pent-up demand, the 1950s were a boom time for the U.S. auto industry. To keep up with tremendous increases in production volume at the Chicago Assembly Plant, a second shift was added in May 1950. By the end of that year, the facility turned out 154,244 cars and trucks, more than any other Ford factory in the world.

This view from 1943 shows gun turrets for M8 and M20 armored cars being made at the Chicago Assembly Plant. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

Business continued to flourish through most of the decade. So, in 1956, company officials announced plans to enlarge and modernize the plant.

“Ford Motor Co.’s Chicago assembly plant will undergo a three-year face lifting that will increase its floor space 42 percent and place it in the select category of plants whose area exceeds 1 million square feet,” said an article in the Chicago Tribune on April 12, 1956. “The work is expected to be completed by the end of 1958 and is designed in progressive stages to minimize disruption of production schedules.

“All told, some 300,000-square-feet of floor space will be added to the building’s present 712,000 square feet…The first phase of the project will be the installation of a new hood, fender and small parts paint system…New facilities for body construction and body painting will follow…When the program is completed, the factory will turn out every model in the Ford line….”

When the project ended, the factory exceeded 1 million square feet, with a two-shift capacity of 720 units daily. That same year, Ford opened a new stamping plant in nearby Chicago Heights.

The 1960s brought further growth, including a 44,000-square-foot expansion in 1962. That was followed by a 34,800-square-foot addition the following year. As part of the project, a 1,185-foot-long floor-level final chassis and assembly conveyor was installed.

Another big change at the Chicago Assembly Plant was the end of truck production in 1964 after 40 years. However, the decade was marred by a bitter 68-day strike in 1967.

On a much happier note, Mayor Richard J. Daley proclaimed Feb. 8, 1972, “Ford Day” in Chicago. To mark the occasion, city, state and local officials gathered at the Chicago Assembly Plant to celebrate the production of its 5 millionth vehicle. The milestone car was a two-door Galaxie 500 hardtop painted gold.

By 1977, the plant became the largest producer of Thunderbirds. A 36,000-square-foot addition in 1977 and a 348,000-square-foot expansion in 1979 increased floor space to more than 2 million square feet. Employment by the end of the decade reached 3,949.

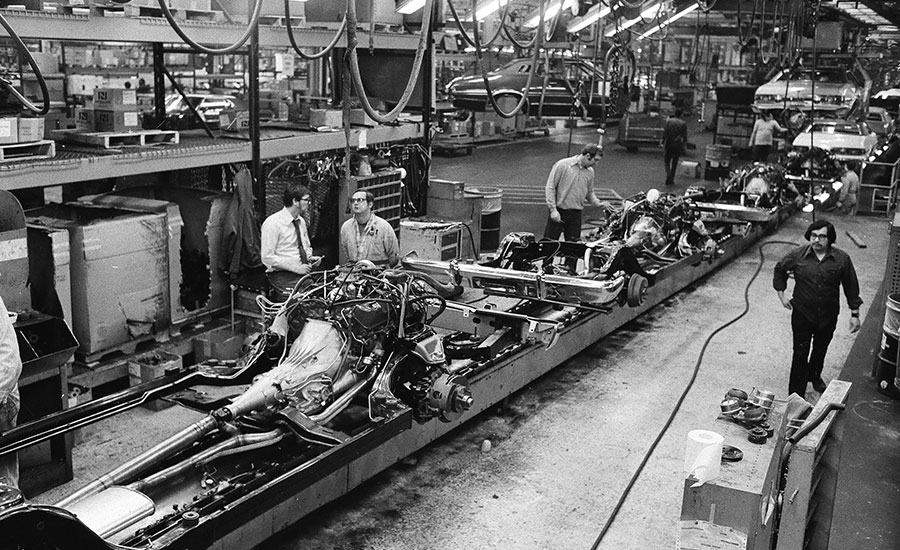

‘Working’ on the Line

Several employees at the Chicago Assembly Plant were featured in Studs Terkel’s landmark book Working, which was published in 1974. The legendary Chicago author interviewed the plant manager and a handful of operators. The book provides unique insight into working conditions at the factory in the late 1960s and early 1970s, before the era of robots, just-in-time manufacturing and OSHA.

The plant manager at the time, Tom Brand, was an engineer who had spent all 30 years of his career at Ford Motor Co. “We build 760 big Fords a day,” he told Terkel. “Assembly’s the biggest division. We’re the cash register ringers. The company is predicated on the profit coming off this line.”

Brand spent a lot of time talking to Terkel about safety initiatives, such as recently enacted mandates that required safety glasses and ear plugs in many parts of the factory.

“There isn’t any car worth a human arm or leg,” he proclaimed. “We can always make a car….Three years ago, I had plenty of grievances. We had a lot of turnover, a lot of new employees. As many as 125 people would be replaced each week….”

Brand, who previously ran Ford’s Twin Cities assembly plant, also talked about his management style and the importance of gemba walks.

“You can’t run a business sitting in the office, ’cause you get divorced too much from the people,'" explained Brand. “The people are the key to the whole thing. If you aren’t in touch with the people, they think ‘He’s too far aloof, he’s distant.’ It doesn’t work….

“If I could get everybody at the plant to look at everything through my eyeballs, we’d have a lot of the problems licked. If we have one standard to go by, it’s easy to swing it around, because then you’ve got everybody thinking the same way. This is the biggest problem of people—communication….”

Terkel also interviewed several spot welders, such as Phil Stallings, who worked on the third shift doing a dirty, dull and dangerous job.

“I start the automobile, the first welds,” explained Stallings. “From there it goes to another line, where the floor’s put on, the roof, the trunk hood, the doors. Then, it’s put on a frame….

“The welding gun’s got a square handle, with a button on the top for high voltage and a button on the bottom for low. The first is to clamp the metal together. The second is to fuse it.

In this view from 1953, the cab of an F-100 pickup truck is being manually welded at the Chicago Assembly Plant. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

“The gun hangs from a ceiling, over tables that ride on a track. It travels in a circle, oblong, like an egg. You stand on a cement platform, maybe six inches from the ground.

“I stand in one spot, about two- or three-foot area, all night. The only time a person stops is when the line stops. We do about 32 jobs per car, per unit. Forty-eight units an hour, eight hours a day….

“The noise, oh it’s tremendous. You open your mouth and you’re liable to get a mouthful of sparks. (Shows his arms) That’s a burn, these are burns. You don’t compete against the noise, You go to yell and at the same time you’re straining to maneuver the gun to where you have to weld….

“I pulled a muscle on my neck, straining. This gun, when you grab this thing from the ceiling, cable, weight, I mean you’re pulling everything. Your neck, your shoulders and your back. I’m very surprised more accidents don’t happen. You have to lean over, at the same time holding down the gun.

“The whole edge here is sharp. I go through a shirt every two weeks, it just goes right through. My coveralls catch on fire. (Indicates arms) See them little holes? That’s what sparks do. I’ve got burns across here from last night.”

Revolutionary Sedans

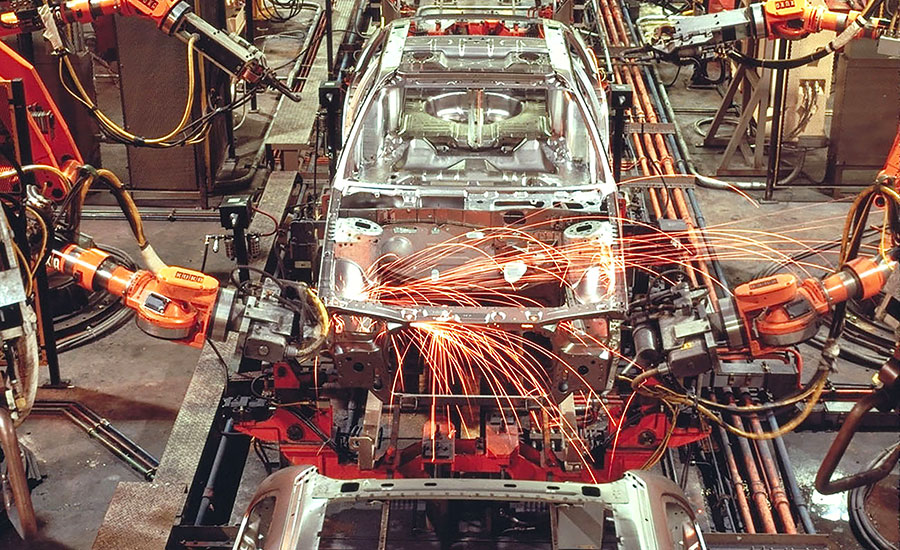

To alleviate those dangerous working conditions, Ford eventually invested heavily in robotic technology at the Chicago Assembly Plant.

An article in the Sept. 30, 1980, issue of the Chicago Tribune said that each vehicle produced at the factory contained “over 5,000 welds per car, 85 percent of them done manually.” At the time, the plant was assembling 800 Ford Granadas and Mercury Cougars per day.

In 1985, Ford undertook a $205 million modernization program to prepare the factory for production of a radically new vehicle. The retooling effort included a state-of-the-art robotic body shop.

“Ford’s Chicago assembly plant had extensive surgery beginning last November in preparation for its new assignment: building the Ford Taurus and Mercury Sable lines,” noted an article in the April 6, 1986, issue of the Chicago Tribune. “Chicago began production of [the vehicles] at the end of January. The high-tech facility…was gutted and remodeled with state-of-the-art assembly equipment, including up to 100 robots…

State-of-the-art welding robots assemble the trendsetting 1986 Ford Taurus in Chicago. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

“The new modular assembly technique…features a door-off line on which car doors are robotically removed after painting to allow automated and human work inside each vehicle. They are replaced after robotic sealing applications.”

When they debuted in 1986, the Taurus and Sable were dubbed “jelly bean” cars, because they featured rounded, aerodynamic styling. The streamlined look appealed to the public and the Taurus quickly became America’s top-selling vehicle.

Compared to its boxy predecessor, the Ford Granada, the Taurus seemed futuristic and sleek, with no sharp corners. Its headlights and fenders were flush into the body, which featured a bold grille-less design and flush window glass.

The midsize sedan broke new ground. Among other innovations, it was the first Ford vehicle in the United States equipped with front-wheel drive. Some experts credit the breakthrough car, which required more than $3 billion in R&D, with saving the automaker from bankruptcy.

In an era sandwiched between the advent of minivans and the debut of SUVs, the Taurus also was the last great American station wagon.

This view from 1964 shows the Ford Galaxie final assembly line. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum, ST-20003083-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection.

Despite several styling updates, the vehicle remained in production in Chicago for 34 years. The last of more than 8 million Taurus sedans rolled off the assembly line in March 2019. It ended up being Ford’s fifth best-selling nameplate, after the F-Series pickup, Escort, Fiesta and Model T.

The retooling effort in 1985 included the installation of state-of-the-art automation. Indeed, more than 100 robotic processes were installed, making the Chicago Assembly Plant one of the most technologically advanced auto factories in the world at the time.

In the 1980s, the Chicago plant also became ground zero in a Ford initiative dubbed “Quality is Job 1.” A new operator training program contributed significantly to quality improvements. Among other things, assemblers were encouraged to analyze and solve problem on the spot and advise management of possible solutions.

An article in the Sept. 30, 1980, edition of the Chicago Tribune described “a totally new quality control system instituted at the plant to insure better products….”

Al Caprara, the plant manager at the time, explained that “10 percent of the total plant is automated. The equipment is 94 to 95 percent reliable. So, normally, errors don’t occur there. But, if there is an equipment malfunction…the equipment is programmed to shut itself down.

“If defects are detected, as many as 2,000 units will be stopped and the defects corrected before they can leave the plant,” claimed Caprara.

Ford Torino chassis roll down the line in 1975. Photo courtesy Chicago History Museum, ST-20003086-0070, Chicago Sun-Times collection

The article explained that “each shift includes 160 quality control people….A laboratory constantly monitors the quality performance of each of six painting stages on the assembly line, seeking to match the peerless performance of Japanese auto production techniques.”

“On the assembly line, a foreman would very infrequently shut down a line for a quality control problem in the past,” explained Caprara. “Defects would be caught later, instead of in the vicinity of the problem.

“Now, we have 12 quality control points, each manned by inspectors, who have the authority to stop the line at any time and have a defect corrected,” Caprara pointed out in the article.

“The foreman and workers are immediately informed on the spot,” added Caprara. “The defect must be corrected and corrective action taken. That way, you don’t get the whole system loaded down with the same kind of defects that could possibly become hidden by subsequent manufacturing operations.”

But, despite those improvements, the plant faced an uncertain future. That’s because the city of Chicago proposed building a new international airport on the South Side in the early 1990s. If the controversial plan had gone through, the factory would have been demolished.

However, new life was pumped into the 71-year-old facility in 1995 thanks to a 200,000-square-foot addition and a $285 million renovation. That initiative paid off when the Chicago Assembly Plant received the 1998 J.D. Power Silver Award and the 2002 Shingo Prize for Excellence in Manufacturing.

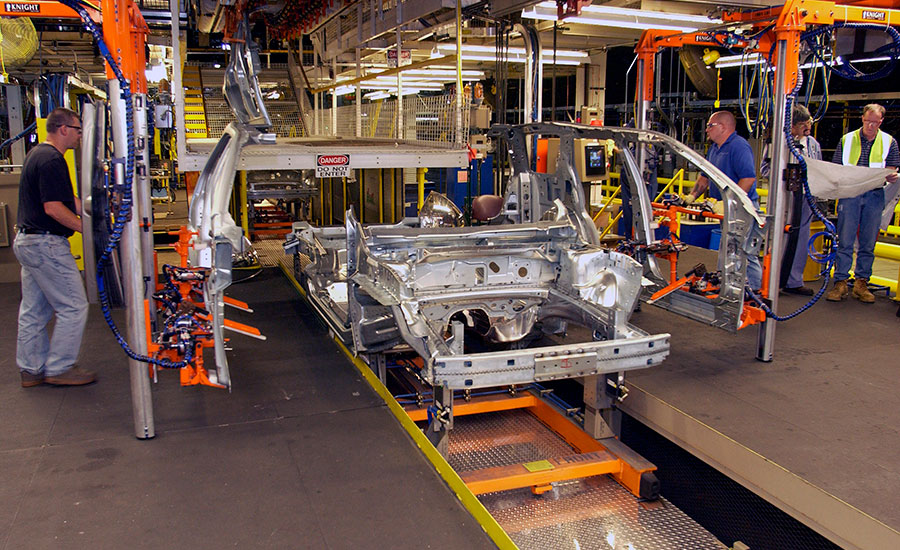

Two years later, a $400 million modernization project included the addition of a flexible body shop and a nearby supplier park.

In 2004, a $400 million modernization project included the addition of a flexible body shop. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

The flexible manufacturing system enabled the plant to produce three distinct models built on one vehicle platform: the 2005 Ford Five Hundred, Ford Freestyle and Mercury Montego.

The body shop underwent a 100,000-square-foot expansion to include new technology such as laser welding for improved structural body rigidity. Laser welding replaced spot welding for roof-to-body weld joints, eliminating the need for access holes in the body side.

The 155-acre supplier park enabled companies such as Brose, Lear and ZF to adopt modular assembly and inline vehicle sequencing processes, making the Chicago Assembly Plant one of the most flexible auto factories in the world.

The decade ended on a high note when Jan Allman became the first woman to run a Ford Motor Co. assembly plant in 2009. That same year, President Barack Obama visited the Chicago Assembly Plant and proclaimed “This plant is part of American history” and “has been a source of deep pride for generations of American workers whose imaginations and hard work led to some of the finest cars that the world has ever known.”

SUV Stronghold

Dedicated employees, a spirit of innovation and agile production lines have helped the Chicago Assembly Plant thrive and survive by continuously responding to changing market conditions and adapting new production technology. For instance, when SUVs became popular 15 years ago, the facility switched gears and retooled once again.

In 2010, Ford invested $100 in the assembly plant and the nearby stamping facility to produce the next-generation Explorer. The popular SUV was built on a flexible assembly line alongside new Ford Taurus and Lincoln MKS sedans.

The most recent transformation occurred five years ago when Ford pumped $1 billion into the two facilities. The assembly plant changeover took one month—a company record for an all-new vehicle build.

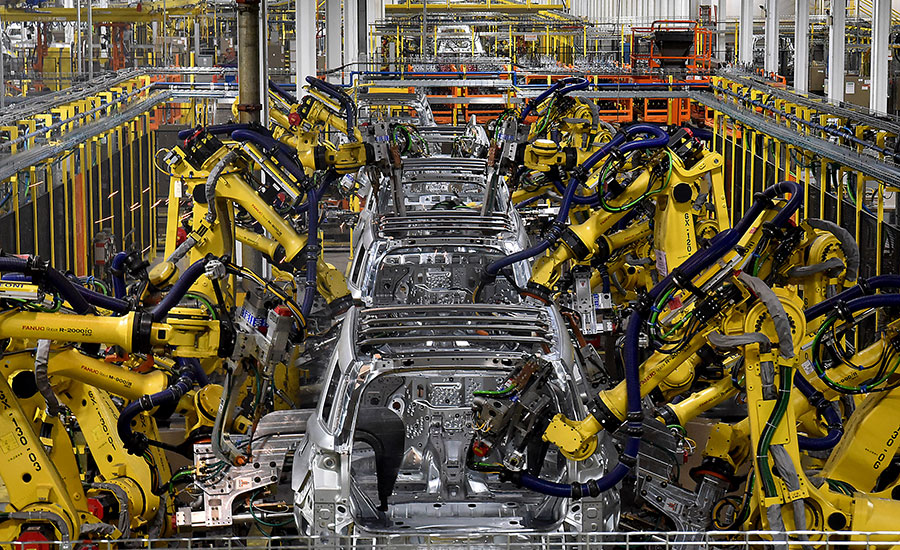

Today, the Chicago Assembly Plant mass-produces sport utility vehicles such as the Ford Explorer and Lincoln Aviator. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

“This reflects American ingenuity at its finest,” said Joe Hinrichs, president of Ford at the time. “In the first five days of the transformation, the team moved the scrap metal equivalent to the weight of the Eiffel Tower from the plant, making room for new equipment.

“Knowing this plant is set in a city and trucks could not go in and out of the plant at all hours, the team got creative and rented a barge, put all of the scrap metal on it, floated it a mile up the river to a recycling center, then moved in more than 500 truckloads of new technology,” explained Hinrichs.

During the 2019 retooling, new state-of-the-art production equipment was installed, such as an automated system for applying urethane to glass. The robots can accommodate eight glass styles for two vehicle models with a common, single unload point.

However, the most dramatic transformation occurred in the body shop, which was stripped down to its concrete floor and completely rebuilt, adding 600 new welding robots. The team updated the paint shop, too, and modified nearly every operator workstation in the final assembly area.

Ford engineers replaced many outdated machines with advanced manufacturing technology, such as 3D printers and hundreds of new error-proofing tools. The plant now also features collaborative robots equipped with cameras that inspect electrical connections during the assembly process.

In addition, Ford invested $40 million for employee-centered improvements to make the plant a better place to work, including all-new LED lighting, cafeteria updates, new break areas and security upgrades in the parking lot.

In 2019, the body shop was stripped down to its concrete floor and completely rebuilt, adding 600 new welding robots. Photo courtesy Ford Motor Co.

One welcome addition were team break rooms on the plant floor. With 30-minute breaks, assemblers used to spend 10 minutes walking to and from an area in which they could relax. Now, they can take full advantage of their entire break period.

Before those improvements occurred, however, the Chicago plant was rocked by scandal in 2015. Years of employee complaints culminated in the replacement of the plant manager, human resources officials and labor relations officers. It was the result of a federal investigation that found evidence to support allegations of rampant sexual harassment and racial discrimination against dozens of female workers.

Today, almost 5,000 people work at the Chicago Assembly Plant, which covers 2.8-million-square-feet. The 113-acre facility serves as the crown jewel in the Windy City’s manufacturing portfolio.

A recent study conducted by the Boston Consulting Group claims that the facility has a huge impact on the local economy, such as supporting more than 60,000 direct and indirect jobs. The Chicago Assembly Plant works with more than 300 suppliers and spends more than $2 billion annually with local vendors.

In the wake of last year’s six-week UAW strike, Ford announced that it plans to invest another $400 million in the 100-year-old factory. However, specific details have not been released yet.

Ford operated an assembly plant in Chicago 10 years before the current facility opened. To learn more about it, see How the Model T Was Assembled in Chicago.

To learn more about other factories that made Chicago a production powerhouse in the 19th and 20th centuries, see Made in Chicago: The Windy City’s Manufacturing Heritage.

Learn about new products for automotive assembly

Precision Link Conveyor for Automotive Parts Manufacturing

IPM Revolutionizes Quality Assurance at Mercedes Benz AG

Automated Robotic Assembly, Brazing & Dispensing Machines

RU Series/Servo Indexing

Blind rivet and Lockbolt Battery Installation tools

Fast, Sensitive, Reliable Leak Detection

Automation Platform for Complex HV Cable Processing

.jpg?height=300&t=1742842937&width=300)