Ford's Rouge Assembly Plant Turns 100

Vertical integration once thrived at Ford’s legendary manufacturing complex.

It has witnessed the production of some of the most iconic vehicles in history. It’s also a veteran of two world wars and the Great Depression. And, it played a pivotal role in American labor history. Ford Motor Co.’s iconic manufacturing complex on the banks of the Rouge River in Dearborn, MI, has seen it all.

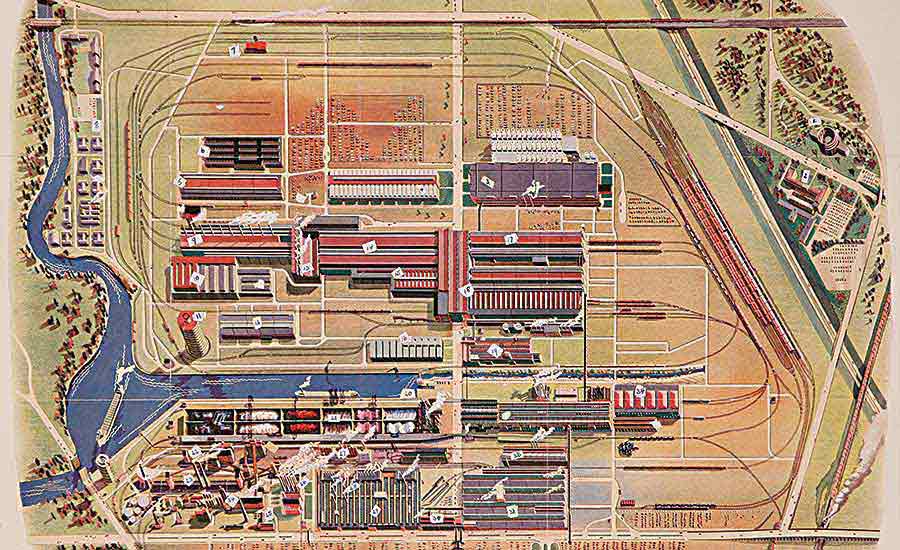

Once upon a time, the Rouge was the only place on earth where you could witness the entire automaking process in one day. The massive facility, which recently celebrated its centennial, was the largest manufacturing operation owned by a single company.

It also was the place where a young engineer from Japan named Eiji Toyoda spent several weeks in the early 1950s. That visit inspired him and his colleagues to create the Toyota Production System.

Since 1918, the Rouge has mass-produced a vast array of vehicles, including automobiles, ships, trucks, tanks and tractors. Three of Ford’s most iconic vehicles have been assembled there, including the Model A in the 1930s, the Mustang in the 1960s and F-150 pickup truck today.

During its heyday in the 1930s and 1940s, the Rouge was a temple of vertical integration. The vast industrial complex included a steel mill, a glass factory, a power plant, a rubber factory, foundries, machine shops, stamping plants and assembly lines. It also included a cement plant, a paper mill, a leather plant and a textile mill.

All totaled, the buildings covered 16-million-square-feet of floor space. They were interconnected by 120 miles of conveyors and more than 100 miles of railroad track. During the height of its operation in 1948, the in-house railroad used 18 locomotives to move more than 1,600 freight cars daily.

Henry Ford called the Rouge an “ore to assembly complex” that hinged on the idea of continuous flow. His idea was to achieve “a continuous, nonstop process from raw material to finished product, with no pause even for warehousing or storage.”

Ford boasted that the Rouge facility featured “the largest completely mechanized installation of handling equipment ever installed in any industrial enterprise.”

At its peak, more than 100,000 people worked at the Rouge. They smelted more than 6,000 tons or iron and made 500 tons of glass every day. A new car rolled off the assembly line every 49 seconds.

Today, the Rouge occupies a smaller footprint. The steel mill and other infrastructure, such as docks, ore bins and unloading cranes, were spun off in 1989. Several Ford manufacturing facilities, including the Dearborn Truck Plant, an engine plant and a stamping plant, currently occupy less than 50 percent of the original 2,000 acres.

However, the Rouge facility is still going strong and is still impressive. The complex, a short drive from Ford’s corporate headquarters and R&D center, is the automaker’s single largest industrial facility. Ford’s flagship factory is also home to its best-selling vehicle.

“To us, it’s more than a factory,” says Bill Ford, executive chairman of Ford Motor Co. “It’s a source of pride for generations of workers who have built the best cars and trucks in the world. It’s an all-American symbol of strength, opportunity and hope; a place where we’ve always been creating tomorrow together.

“This is where the industrial revolution took hold,” claims Ford. “My great-grandfather’s vision for the Rouge was a fully-integrated, self-sufficient manufacturing powerhouse.

“Whatever future our employees dream up and design, one thing will remain a constant: We’ll build it at the Rouge,” adds Ford. “The Rouge was our most important plant 100 years ago. It’s our most important plant today. It will be our most important plant tomorrow.”

Vertical Integration

The Rouge was once the equivalent of vertical integration on steroids. Henry Ford’s ultimate goal was to achieve total self-sufficiency by owning, operating and coordinating all the resources needed to produce complete automobiles.

Two main forces prompted Ford to develop the vertically integrated facility, which was the largest, most efficient manufacturing complex of its time.

Henry Ford had a tumultuous relationship with suppliers. When John and Horace Dodge (key suppliers of early Model T bodies and chassis) decided to start producing their own vehicles in 1914, Ford was furious.

A few years later, World War I also demonstrated how vulnerable Ford Motor Co. was to supply shortages. The legendary Highland Park plant (home of the Model T and the world’s first moving assembly line) suffered a number of work stoppages because of supplier failures.

Henry Ford was determined to fix the problem. His solution was vertical integration.

Ford embarked on a crusade to create a manufacturing juggernaut that would eliminate the need for third parties. He acquired coalfields in Kentucky and West Virginia, plus iron ore mines, forests and lumber mills in Northern Michigan. Ford also developed a controversial rubber plantation in Brazil. To transport all those raw materials to Detroit, the company purchased a large fleet of railroad cars and cargo ships.

Ford also bought up several thousand acres of land along the Rouge River southwest of Detroit and converted it into a self-contained manufacturing city. Between 1919 and 1926, it grew to include 93 buildings capable of producing 4,000 vehicles per day.

The original Rouge complex was a mile and a half wide and more than a mile long. The foundry alone covered 30 acres and employed 10,000 people.

“Ford Motor Company’s monument to saved minutes was the River Rouge plant,” says Douglas Brinkley, an historian and author of Wheels for the World. “It was not only the most important factory at the company, it was the most important in all of industrial America.

“Other plants were built or constructed,” notes Brinkley. “River Rouge was created: a world engineered from a blank sheet of paper, intended to allow the maximum number of operations without wasted time, effort or cost.

“The secret to saving money at the plant lay in synchronizing the various levels of transportation,” adds Brinkley. “A predictable flow of parts and materials—from the source, even in another state, all the way to the line where they were needed—reduced the need for long-term storage.”

However, the first product to roll off the Rouge assembly line was not an automobile: It was a ship. Ford built Eagle-class submarine chasers for the U.S. Navy at the tail end of World War I. Three assembly lines, each capable of carrying seven boats at a time, produced the 204-foot vessels. Each ship required 260,000 rivets.

Before the last ships were assembled in 1919, Ford moved auto body-building machinery into the buildings, which were later transformed into chassis assembly lines. The first wheeled vehicle assembled in the facility was the Fordson tractor.

In the mid-1920s, Ford shifted automobile assembly from the Highland Park plant to the Rouge complex. By the time production of the new Model A ramped up in 1928, the Rouge was the heart and soul of Ford’s manufacturing empire.

A few years later, when the U.S. economy and auto sales took a nose dive during the Great Depression, vertical integration proved to be an Achilles heel for Ford. It had a harder time cutting costs compared with other automakers that relied more on outside suppliers.

While Ford’s goal of self-sufficiency was never realized, no company has ever come so close on such a grand scale. But, several other manufacturers tried to copy the vertical integration concept.

For instance, International Harvester Co. also made many parts and components in-house. In addition, the agricultural equipment manufacturer owned and operated its own steel mill (Wisconsin Steel on the Southeast Side of Chicago), mines and a fleet of ore freighters.

Conveyors Galore

Unlike Ford’s Highland Park and Piquette Avenue plants, which were multistory factories where the moving assembly line was developed and perfected, the Rouge featured one-story buildings that did not require elevators, ramps and hoists to move materials up and down.

“[Ford] was adamantly opposed to unnecessary effort, especially in moving materials,” says Brinkley. “He argued that a one-story building allowed for the smoothest movement of materials past men and machines.”

Advanced material handling systems were one thing that set the Rouge apart from all other factories. Some observers in the 1920s compared it to a “great water supply system, with mains and many feeder pipes,” Brinkley points out.

“More efficient assembly was possible on one floor, and there was little need for all the fireproofing, corrosion resistance and vibration damping that made reinforced concrete so valuable in tall buildings,” says Patrick Malone, co-author of The Texture of Industry.

“Steel framing was strong and easy to erect, and it took up less space than concrete,” adds Malone. “The wide roof trusses that could be built with steel allowed [engineers] to dispense with supporting columns, thus allowing more flexibility in equipment layout.”

Architect Albert Kahn managed to add a sense of light and air to many of the buildings by using the Pond truss. This tall, distinctive M-shaped roof was engineered for maximum performance in ventilating and lighting the factory interior.

One of the first structures constructed at the Rouge, the B building, marked a milestone in plant layout. The 1,700-foot-long facility was the first to enclose an entire Ford manufacturing operation in a single structure and on one floor. It was also Ford’s first steel-framed structure, which allowed it to be expanded more easily than contemporary industrial buildings made with reinforced concrete.

“Ford erected very large single-story factories to avoid the cost of hoisting materials and to allow bigger uninterrupted spaces, since columns to support upper floors were no longer needed,” says Joshua Freeman, author of Behemoth. “The expansive, open areas gave engineers flexibility in machine placement, aided by the company decision to stop using overhead shafts and belts to power machinery, instead deploying individual electric motors.

“Single-story plants avoided the need to punch holes between floors when assembly lines were repositioned,” adds Freeman. “Ford [also] spaced the Rouge buildings far apart to allow for later expansion.”

Kahn and the builder, William Verner, worked closely with Ford production engineers to lay out the floor plan of the Rouge plants.

“The factory’s overall design was functionalist, but the use of floor space wasn’t rigidly preconceived,” says Dave Nye, author of America’s Assembly Line. “Verner laid out each section of the factory in consultation with the managers of each process. The flow of the work determined the placement of each building.”

“Managers tried to get rid of buffer inventories,” adds Nye. “[They] studied the setup of machinery so there was no wasted space. [They] tried to move the machines as close together as possible to eliminate the movement of work.”

“Transportation inside each building was based on a network of conveyors and cranes that allowed materials to flow in a steady stream where they were needed,” says Brinkley. “Mechanized handling equipment made River Rouge as precise as a Swiss watch—and made it look from an aerial vantage point not unlike the inside of one.”

The complex featured a wide array of overhead and floor-based gravity, spiral and bucket conveyors, in addition to moving belts, moving platforms and overhead cranes that automatically moved parts and components throughout the vast complex.

“Every department was equipped with mechanical handling devices, and every shop and building was connected by a network of overhead monorails and conveyors,” says Lindy Biggs, author of The Rational Factory. “Engineers at the Rouge designed many different types of handling technologies, most of which were extensions of devices first developed at Highland Park.

“At the Rouge, engineers…almost eliminated hand trucking,” adds Biggs. “Overhead conveyors…played the greatest role in ending hand trucking. They became an important part of the Rouge production system.

“By maintaining a constant supply of parts for the worker, overhead conveyors did away with the necessity of storing parts at each workstation,” explains Biggs. “More importantly, they eliminated most trucking of parts, thereby improving reliability and speed of production.”

Learn about the Rouge today, including a behind-the-scenes look at how the Ford F-150 pickup truck is assembled.

Read how the Rouge assembly plant was revitalized 15 years ago.

See an old film about the Rouge in action during the late 1930s.

Watch a video of manufacturing operations at the Rouge in the early 1960s.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!