Home » Keywords: » friction welding

Items Tagged with 'friction welding'

ARTICLES

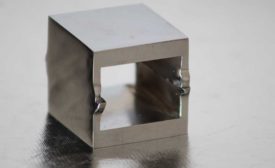

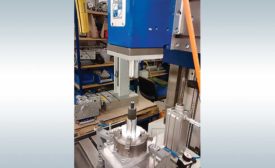

Flexible Assembly Machine Combines Multiple Plastics Joining Processes

What if one machine could be configured to perform any friction-based welding process with a simple change of tooling?

September 12, 2017

Never miss the latest news and trends driving the manufacturing industry

Stay in the know on the latest assembly trends.

JOIN TODAY!Copyright ©2025. All Rights Reserved BNP Media.

Design, CMS, Hosting & Web Development :: ePublishing