Wrap It Up! New Machines Tape Wire Harnesses

A new generation of taping equipment is making short work of wrapping wire harnesses.

This semiautomatic machine can apply tape up to 1.5 inches wide at speeds of up to 14 fpm. Photo courtesy CAM Innovation

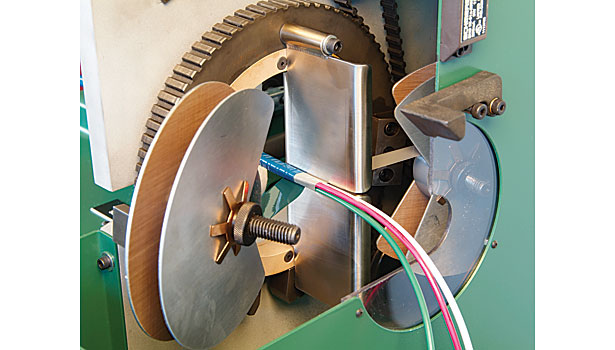

A dual-head machine can apply two tapes simultaneously or a combination of foil and tape. Photo courtesy CAM Innovation

This semiautomatic machine lets engineers set parameters such as overlap length and taping speed. Photo courtesy Ondal Tape Processing GmbH

Semiautomatic taping machines are faster and more consistent than manual processes. Photo courtesy CAM Innovation

Hula hoops, irrigation hose, golf clubs and the exciter coils for generators on nuclear submarines. These are just a few of the extraordinary products that have been wrapped with tape using equipment designed and built by CAM Innovation.

But, it’s the machines for taping ordinary assemblies—wire harnesses—that keep customers coming back for more. “After purchasing our equipment, our customers will call to say they’ve taped more harnesses in two days than they have in the past month,” boasts Scott C. Brickell, sales manager at CAM Innovation. “When I sell a guy one machine, he’ll often come back and buy more.”

There are many reasons to apply tape to a wire harness. Spot applications of tape can be used to attach plastic clips to a harness, to mark a key location, or simply to bundle wires together in lieu of cable ties.

In many cases, particularly in the automotive and aerospace industries, a section of the harness—or even the entire assembly—will get wrapped in tape. The main reason to wrap a harness is protection. Tape provides an extra layer of insulation from heat, moisture, chemicals, abrasion and electromagnetic interference. Another reason to wrap harnesses with tape is to dampen vibration and prevent squeaks and rattles.

“A wrapped harness is pressed together to the smallest possible diameter,” adds Hubert Eckart, business manager of Ondal Tape Processing GmbH. “This is very important in automotive applications. Taping compresses the harness, but allows it to remain flexible so it can be placed easily in the car.”

Compared with other methods for safeguarding wire harnesses, tape is easier to apply and affords greater protection, says Eckart. Heat-shrink tubing is difficult to apply to an entire harness. Plastic split loom is awkward to handle and does not compress the wiring.

“Harness protection using tape simplifies logistics,” says Eckart. “Only a tape roll is needed. Precut lengths of material are not necessary.”

Tape Types

Harness tapes are made with a variety of backing materials and pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs) to suit specific application needs. Harness tape is typically 0.75 inch wide and supplied on standard rolls of 50 or 100 feet. Many tapes are available in a variety of colors, enabling harness designers to color-code breakouts.

PVC is the most common backing material for harness tape, but a variety of other materials are also available, including cloth, felt, foam and foil.

Felt and cloth tapes are good for sound-dampening and high-temperature applications. Cloth backing can be made from natural fibers, such as cotton, or synthetic fibers, such as rayon, PET and glass.

PSAs include acrylics, silicones, and natural and synthetic rubber. The latter are best for temperatures below 105 C. Acrylic PSAs can handle temperatures up to 125 C, while silicone PSAs are good for temperatures exceeding 125 C.

Choosing a tape is a matter of finding the right combination of backing and PSA to match the application requirements. For example, Tape 363 from 3M consists of a transparent silicone PSA and a backing of aluminum foil (1 mil thick) laminated to glass cloth (2.4 mils thick). Designed for aerospace and other extreme applications, the tape maintains its effectiveness in temperatures ranging from -54 to 316 C.

Polyken 22HA from Berry Plastics Corp. is designed to resist abrasion in high-vibration applications, such as automotive engine compartments. It consists of a polyester cloth backing and an acrylic PSA.

“Virtually all of our machines can be used with any kind of tape,” says Brickell. “Some tapes, such as paper tapes, might need special guide rollers. But, 80 percent of what we apply is vinyl electrical tape.”

Equipment Options

A wire harness can be taped manually—just a worker with a roll of tape—but the process is time-consuming and the results are inconsistent. It also puts workers at risk of wrist injuries. Machinery is a better option.

“When taping a wire harness, you want a consistent overlap of the tape, and that’s something you can only get with a machine,” says Brickell. “When you’re doing it by hand, the taping quality will vary as the day wears on. Workers get tired. A machine wraps a harness the same way every time.

“I’ve seen some very fast hand-tapers, but machines can do about 14 fpm with perfect overlap.”

Maintaining a consistent overlap is not just a matter of looks. Inconsistent overlap can cost a harness assembler thousands of dollars in wasted tape. On average, a manual taper will use 25 percent to 40 percent more tape than is necessary, Eckart points out.

“That can easily amount to $1,000 per person per year, which justifies the cost of a taping machine,” he notes.

That said, not every application is suitable for automation. “If only a small area needs to be taped, it’s not practical to do it with a machine,” concedes Brickell. “It also depends on the thickness of the harness. If what you’re taping varies widely in thickness—if it goes from 1 inch in diameter to 3 inches to 1 inch and then to 4 inches—it’s going to be difficult for a machine to tape.”

Taping equipment options run the gamut from simple hand tools to manually fed benchtop machines to fully automatic systems. There are single-roll machines, dual-roll machines, and machines that handle tapes with release liners.

At the low end of the spectrum, there’s the HandTaper from Ondal. This ingenious pistol-grip hand tool can be used to manually wrap harnesses as thick as 20 millimeters in diameter. Though it’s not motorized, it does maintain constant tension on the tape during wrapping. Instead of awkwardly transferring the tape roll from hand to hand around the harness, the operator inserts the harness into the center of the tool and then simply moves the tool in an up-and-down circular motion. The lightweight tool accepts tape ranging from 9 to 19 millimeters wide.

“It takes a little practice, so operators should be trained to use the tool,” says Eckart. “But, the effort is worthwhile in terms of more consistent quality and fewer repetitive motion injuries.”

Later this year, Ondal will introduce a motorized version of the HandTaper. An early version was unveiled in May at the National Electrical Wire Processing Technology Expo in Milwaukee.

A step up from a hand tool is a machine like the CT motorized spiral taper from CAM Innovation. The tape head, which looks like a pillow block bearing with an extra-wide opening, is mounted on top of a worktable. The tape head is driven by a variable-speed DC motor with a maximum speed of 600 rpm. A foot pedal beneath the table activates the tape head and governs its speed, like the foot pedal for a sewing machine. (Decades ago, the tape head was powered by a treadle mechanism.)

Three models are available: one for harnesses up to 0.375 inch in diameter, one for harnesses up to 1 inch in diameter, and one for harnesses up to 2 inches in diameter.

The operator pulls the harness through the tape head while controlling wrap speed with the foot switch. The amount of tape overlap depends on how fast the operator moves the harness through the head. At 600 rpm with a 0.75-inch wide tape and a 0.5 inch overlap, the maximum taping speed is 3 ips.

To move up from a tabletop, manually fed machine, assemblers can opt for a semiautomatic, benchtop machine like the VarioMaster from Ondal or the RHT spiral taper from CAM Innovation. The latter machine can apply tape up to 1.5 inches wide at speeds of up to 14 fpm. For greater productivity, a dual-head model can apply two tapes simultaneously or a combination of foil and tape.

To tape a harness, the operator opens the safety cover, places the harness into the tape head, and engages a pair of drive rollers. Then, the operator closes the cover and steps on a foot pedal to start taping. The rollers clamp down on the wires and pull them through the tape head. An encoder keeps the rollers and tape head in synch with each other, ensuring a consistent tape overlap at any speed. The amount of overlap is set with a digital ratio controller.

Breakouts are pulled through an opening in the safety cover. When a breakout reaches the tape head, the operator switches off the machine, pulls the breakout past the head, and resumes taping. The safety cover does not have to be opened.

“That’s a nice little feature,” says Brickell. “The operator can get past the breakouts very quickly. When he gets done taping the main trunk, he can go back and tape all the breakouts.”

Of course, automation comes with a price. At approximately $20,000, the semiautomatic machine is twice the price of the manually fed one.

Which part of the taping technology spectrum is best for your shop depends on what is being taped, says Eckart. Short, simple harnesses can be taped quickly with a manually fed, tabletop machine with a closed head. Long harnesses require feed rollers for more consistent overlap. Complex harnesses with multiple branches require a manually fed or semiautomatic machine with an open head.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!